The history of design in Canada is a largely undocumented and undiscussed topic in design studies. Not only do Canadian designers and design academics often overlook their own history in favour of European or American design history, there is little to no study of Canadian design found outside of Canada. While this is problematic in terms of lacking information to construct a ‘canon’ of Canadian designers, it remains even more problematic in identifying and placing importance on a century or more of design that has been produced anonymously. This anonymous design, found in magazines, toys, games, catalogues, and other items used by Canadians everyday throughout the 20th century, profoundly intervened in the daily experience of Canadians. Everyday experience in Canada at the beginning of the 20th century often — if not always — included interaction with the Eaton’s mail order catalogue. This catalogue, a formidable paradigm-shifting element in Canadian daily life beginning in 1884, conflated consumerism with concepts of modernism, progress, and the duty of citizens to contribute to their nation’s economic well-being. In her book Retail Nation, Donica Belisle connects the rise of mass retail enterprise and a new attitude towards consumerism to the early formation of Canada as a modern nation, while emphasizing the progression of innovation through “three realms of the marketplace, namely, production, distribution, and consumption” [1].

If the role that department stores and their catalogues play is academically and historically vital in the nation building history of Canada, why do we downplay the importance of everyday, popular culture, and household items that are often ignored in design histories or taken for granted? Canadian design was, and still remains, an intrinsic aspect in the manufacture, production, distribution, and promotion of these goods on display in department stores and throughout their mail-order catalogues. The cultural influence that Eaton’s exerted on Western Canada in particular could not have been accomplished without a large number of product designers, graphic designers and illustrators, architects, and — while they may not have been described as such in their own time — systems designers, who were able to orchestrate and build supply and distribution networks with a very limited rail and roadway system.

Achieving Authenticity

“Authenticity is to be understood as an inherent quality” [8]. Defining what an authentic and significant moment in Canadian design history might be requires a definition of authenticity as a term, and the context in which we might attribute it. While narratives and anecdotes supplied by those who interacted with the Eaton’s catalogue may describe an authentic experience, validation and recognition from academics and designers is necessary to create a unified practice of identifying and sharing information. As Charles Lindhom states, “authenticity gathers people together in collectives that are felt to be real, essential, and vital, providing participants with meaning, unity, and a surpassing sense of belonging” [5]. Along with other academics who have focused on the concept of authenticity, Lindholm references Lionel Trilling[1] who writes that notions of authenticity grew out of concepts of sincerity. Relating authenticity to sincerity is a complicated task, however, because it implies that in order to achieve authenticity we must qualify it through experiential terms, rather than confirm it through a quantifiable — and therefore verifiable — method.

The rise of scientific reasoning in the modern era meant that collected data soon became the prime evidence to confirm perceptions of authenticity, relegating notions of intuition and emotion to irrelevancy. Within this context, Canada emerged from the 19th century as a newly unified nation, emphasizing the importance of production and consumption in modern culture. “Historians have paid substantial attention to some aspects of modernization, especially urbanization, industrialization, and the expansion of the federal government. Still underexplored, though, are the ways mass merchandising changed Canadian life during this time” [1]. If the modernist values extending from urbanization and industrialization in Canada did indeed influence the way in which we valued and recognized —or in fact, did not recognize or value — the cultural contribution made by everyday merchandise found in catalogues, then we are left with the task of piecing together an authentic account of Canadian design through oral histories, inconsistent documentation, and speculation.

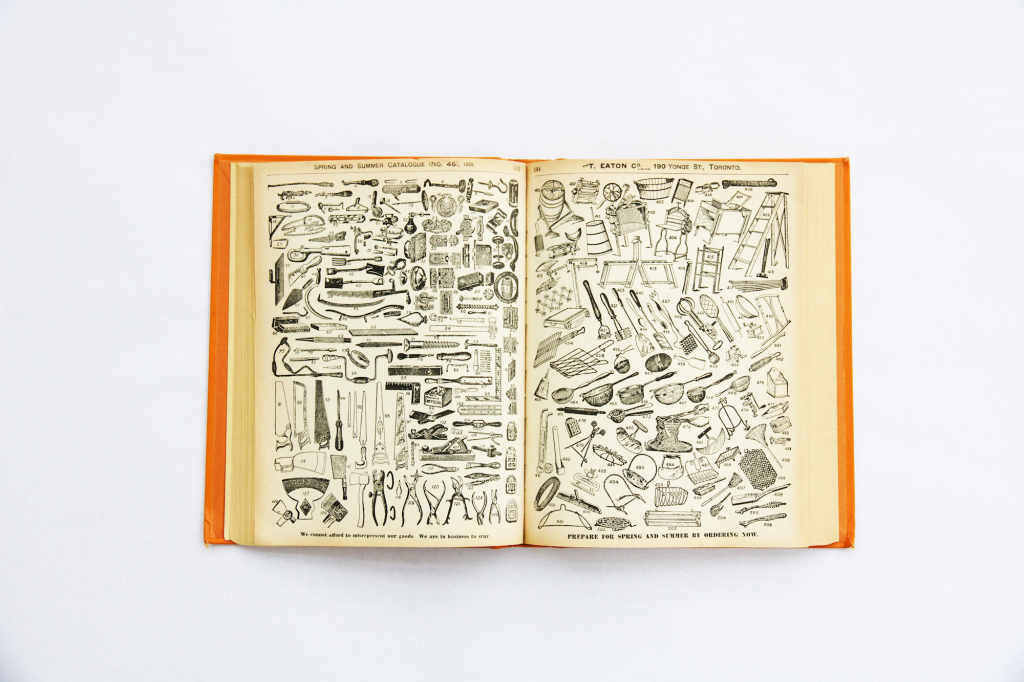

In many cases, individual illustrations such as the ones contained in fig. 1 may not be significant enough to make an authentic contribution to Canadian design history. There are other ways to evaluate these illustrations, however. We could consider the entire page of illustrations as an inter-dependent body of work. We could place the image —or group of images — within the context of emerging technology. We could evaluate specific items as unique and only available in this catalogue. Finally, we could also place these individual objects within an innovative system (ordering goods through the mail) that not only takes advantage of newly formed supply systems, but plugs into a DIY system that has gone beyond what most contemporary retailers today expect from their consumers. While “authenticity can be ratified by experts who prove provenance and origin, or by the evocation of feelings that are immediate and irrefutable” [5], the concept of authenticity in design history requires an understanding of the cultural context in which the work resides. In fig. 2, we can consider this kind of mason jar as an authentic contribution to design history when we take the various kinds of design working together —graphic design (labels), the design of the glass vessel, and the design of the wire and sealing system for the jar — and understand the value of the jar within an early 20th century Canadian culture that relied on the preservation of food throughout various seasons.

Acknowledging the Alternatives

Very few, if any, design historians have situated the importance of anonymous, or unattributed, Canadian design within the broad landscape of design histories. In Brian Donnelly’s article, Locating Graphic Design History in Canada, he writes about the importance of Canadian designers relying on an oral tradition in their practices, not only in the form of training and mentorship, but also as a way to compile histories. This does not place the concept of orality in opposition to a written canon of Canadian design, but instead considers it as a contribution to a broad range of methods, capable of expanding our knowledge and understanding of our cultural history.

The uncertainty between authentic/acknowledged design and unacknowledged — and therefore less authentic — design is a continuation of the tension between high culture and low culture, and the perception that only some design work is culturally more valuable. When Raymond Williams declared “culture is ordinary, in every society and every mind” [9] in 1958, he was declaring his opposition to the bifurcation of culture in everyday life into “high culture” and “low culture.” The ordinary work of designing and manufacturing products, illustrating these products for publication, designing and producing a catalogue, and then developing systems of distribution for both catalogue and its contents is a remarkable achievement with a profound and resounding cultural effect. Angela Davis’s book, Art and Work, describes the prolific commercial illustration industry in Winnipeg in the early 20th century, where at least one studio, Brigden’s, employed 65 artists, 25 engravers and five photo-engravers at their busiest seasons. These artists were often hired without any previous training whatsoever, and learned to illustrate as apprentices on the job. “The graphic design tradition in Canada, then, could be said to be an oral tradition in two senses: it has been informally transmitted, primarily through studios, schools and periodicals, without having been permanently collected, curated or canonized in print or by institutions, and it is only now being gathered up again as an oral history from the practitioners themselves” [4].

For the Eaton’s catalogue, oral histories contribute valuable information at many levels. They can contribute valuable information about how the catalogue was conceived and constructed, they can relay the experience of consumers in interacting with the catalogue itself as well as the goods portrayed in the catalogue, and finally, oral histories can capture the nostalgia that seems to be intrinsic to remembering what it was like to live with the catalogue every day. If we were to compare these assets to American or European design history canons, we run the risk of mistaking orality with a lack of literacy, which devalues the possibilities of enriching Canadian design history. Equally distressing, where design is indeed documented in print — and therefore literate — but represents the ordinary or everyday, it is often mistaken for an inauthentic contribution to our culture.

Everyday Standards and a Constructed Visual Vocabulary

Everyday design, such as the kind found in Eaton’s catalogues, constructed a visual vocabulary for its consumers that influenced their daily life. The catalogues provided standards — a constructed measure of how people ought to live — through the display of commodities and a narrative of modern progress. Because these standards were narrated en masse through the visual vocabulary of each catalogue, designers were ultimately responsible for their role in developing common cultural relationships between Canadians citizens and objects and materials.

Post-World War II saw many new retail products, thanks to injection mould techniques, and new plastic materials. Toys such as the ones made by Peter-Austin Manufacturing company (fig. 3) and Reliable Plastics evidently emphasize the manufacturing capability in Canada, but not necessarily the innovation or originality in the design of the toy itself. For instance, there is no design information to inform us about the toy featured in fig. 4. It was featured in the 1953 Reliable Plastics catalogue, but it is unclear whether the design of the toy was original or if it copied other popular toys in its time. The catalogue description boasts that this ukulele can be played like a real instrument, but also that it is ‘moulded in beautiful assorted colours’. The emphasis of the material over the design is an artifact of a time where plastic was still an emerging and exciting material. As with the products from Reliable Plastics, Medalta and Hycroft potteries products were equally pervasive and influential in Western Canada. The factories for Medalta and Hycroft were located in the clay district in Medicine Hat, Alberta, which was about 150 acres in size, and was the site of massive productions of clay products, from home goods to clay sewer pipes. Some of the ceramic designers are known in the histories of the various factories in this district, however many of the crafts people remain anonymous. These crafts people are part of a larger oral history that describes their role in producing some of the most popular and ubiquitous objects for homes in Western Canada. As a part of equating consumption of products as a citizen’s duty, the notion of basic standards of living arose around the same time as catalogues began to be distributed in Canada. This is thanks to the proliferation of etiquette books and magazines, but also due to an emerging cash economy in the west combined with new access to retail goods, such as mail order catalogues.

In her book Standard of Living, Marina Moskowitz states that “the standard of living was not a measure of how people lived, according to what they could afford—it was a measure of how people wanted to live according to shared cultural minima” [6]. In keeping with setting or improving living standards, hybrid tent/homes were developed during a time when many families in the west were still living in temporary housing, such as sod houses. Developing a standard of housing by selling a prefabricated home was another huge undertaking by many mail-order catalogues in the early 20th century. From 1910 to 1932, Eaton’s supplied sold house plans and all the lumber and supplies needed to build the house. Again, the designers who not only designed and produced the plans for the houses, but orchestrated the delivery system of every supply needed to build these homes, have not been give sufficient acknowledgement for developing a complex DIY system in Western Canada. Eaton’s sold at least 40 different house plans, with varying levels of sophistication. These mail order homes remain a legendary aspect of the history of urban development in Western Canada, “many of them serving the fourth or fifth generation of the same family” [2]. The documentation of the homes themselves in addition to the oral histories of the occupants have been largely taken up by local historians, and are most often contextualized within the framework of local histories rather than within the broader concern of Canadian design history.

If the recent history of Canada is so uniquely tied to the production, manufacturing, distribution, promotion, and consumption of material goods, it remains a mystery why design and designers are now not necessary valued in the public sphere as an implicit part of this nation-building or nation-maintaining system. While the contribution of specific designers and their work in their industry, community, and Canadian culture in general, remains important to identify and record, it behooves designers to also point out that the work produced in anonymity throughout the 20th century have made a major contribution to our material and visual landscape. Our manufacturing history, our relationship with plastics and our relationship with natural materials that are regional and imbedded within culture become lost without a historical account.

Embracing the Anonymous

If design was a significant component in “enhanc[ing] democratic life, strengthen[ing] the Canadian nation, and creat[ing] citizen fulfillment” [1] one hundred years ago, there is very little reason why it shouldn’t continue to be valued as a component in nation building and cultural contributions now. The roots of Canadian design, no matter how sophisticated or mundane it may be perceived, is located within the acquired material wealth of the average Canadian over the past century. While much of the work discussed in this essay can be criticized as merely nostalgic, mass-produced, unsophisticated, and ordinary, I argue that these works have contributed to a shared visual vocabulary across Canada, and therefore a shared, collective culture worth acknowledging.

These designed objects mediate daily life. They set standards. They contribute to a complex visual language to the average citizen, and they move through time and space often unacknowledged and more often than not, unattributed. They are a part of our collective heritage and if we begin to acknowledge the current ordinary objects that we depend upon on a day-to-day basis even now, we will see that they remain a part of a collective and authentic everyday experience.

References

- [1] Belisle, D. Retail nation: Department stores and the making of modern canada. Vancouver, BC Canada: UBC Press, 2011.

- [2] Canadian Heritage Information Network. Mail Order Houses: The T. Eaton Co. Ltd, 2013. http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/edu/ViewLoitDa.do;jsessionid =74C7A5F56740787D6AA976F073028A22?method=preview&lang=EN&id=24759.

- [3] Davis, A. Art and work: A social history of labour in the canadian graphic arts industry to the 1940s. Montreal and Kingston, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1995.

- [4] Donnelly, B. Locating graphic design history in canada. Journal of design history, 19 (4), 2006. 283-294.

- [5] Lindholm, C. Culture and authenticity. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 2008.

- [6] Moskowitz, M. Standard of living: The measure of the middle class in modern america. Baltimore, MD, USA: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008.

- [7] Robinson, D. J. (Ed). Communication history in canada, (2), Toronto, ON, Canada: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- [8] Vannini, P., and Williams, J. P. Authenticity in culture, self, and society. Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2009.

- [9] Williams, R. Culture is ordinary. In B. Highmore, Everyday life reader. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. 91–100.