Abstract

This article examines how participatory design strategies can serve as an effective tool when working with multiple design constraints. Emily Carr University of Art + Design students were asked to collaborate with children with special learning needs to create a textile-based product from reclaimed fabric that endorsed sustainability among both the users and the designers.

Kenneth Gordon Maplewood School (KGMS) is an independent school that specializes in teaching children with dyslexia and learning disabilities. Owned and operated by The Society for the Education of Children with Specific Learning Disabilities, KGMS employs the Orton-Gillingham teaching method, which favours visual, auditory, tactile and kinesthetic cues. [2] In 2010, KGMS relocated from Burnaby, British Columbia to its present location in North Vancouver, BC.

Second-year design students from Emily Carr, working in pairs, were asked to create an interactive textile-based artifact or system that would encourage sustainable practices within the KGMS community. Each team was matched with a group of three to four Division 6 students from KGMS, who would serve as co-creators on the project. The resulting design would be gifted to KGMS and its students for implementation in their school.

Defining the Problem

Prior to this project, the majority of our design briefs have been directed towards theoretical users and allowed for “blue sky” ideation—designing without limits. In order to gain practical experience, we were challenged to apply our knowledge and skills to a set of complex, real-world issues that contained multiple non-negotiable parameters. Working with users with very specific needs and limitations, we were asked to use participatory design techniques to create a product that not only encouraged sustainable practices, but considered such practices in all facets of the production process as well.

The project was subjected to numerous constraints. Our product had to:

- be made from reclaimed Sheerfill II-HT fabric (a fiberglass and polytetrafluoroethylene composite) from Canada Place’s former roof, donated by Re-Fab Vancouver;

- use only textile manufacturing techniques;

- not exceed 2 square metres in size;

- be made of repetitive elements;

- emphasize dynamic relationships;

- be geared towards children, factoring in ergonomics, safety, functionality and durability; and

- take into consideration the learning needs of the KGMS students.

Methodology

Preliminary Research

In order to present sustainability to the students in tangible, accessible terms, we elected to focus on environmental issues that were common to our region. Given KGMS’ proximity to the Burrard Inlet, we narrowed the initial scope of our research to environmental issues related to water, such as consumption, conservation and marine debris.

Cultural Probe

Based on our research findings, we created a cultural probe for each KGMS student that consisted of a team-building puzzle, exploratory drawing and collage exercises, a scavenger hunt and an ideation activity involving common recyclable objects. These probes, which would provide glimpses into the everyday lives of our students, were intended to serve “as beacons for [our] imagination.” [1, 3]

After receiving the completed probes back, we discovered that while our KGMS group was aware of the environment, their knowledge was limited to abstract recycling practices typically associated with public advocacy campaigns. Furthermore, they expressed little interest in the subject of water, rendering our preliminary research moot. Rather than relegate our students to the role of mere users, we abandoned our initial concept in favour of creating a co-design space at this early front end of the design development process where the KGMS students would work with us in a more emancipatory role. [4, 5]

Co-Design Sessions

To encourage free-form dialogue that would reveal potential design opportunities, we organized two co-design sessions that alluded to sustainability as a by-product of each activity rather than the focus.

The first session consisted of:

- a student-led tour of KGMS;

- a figurine workshop where each student:

- created a superpower character using found objects and scrap material; and

- after classifying their character as a hero or villain, determined what their character would do if it was on a planet with no trees, plants or water; and

- a round robin storyboarding exercise that was altered on site, based on the student’s interests, into a friend-or-foe workshop where each student created an accessory, companion or enemy for their original character out of modeling clay.

The second session consisted of a material and form exercise that bore similarities to our own design exploration with Sheerfill II-HT fabric. Using only the scrap textiles we provided, the KGMS students were asked to make something out of at least two pieces of fabric that were connected together without the use of adhesives or fasteners.

Findings

The topic of superheroes dominated our co-design sessions. Rather than attribute this to a child’s preoccupation with fighting and adventure, however, we considered the subject from our students’ perspectives. Society, in general, regards literacy as a threshold indicator of success in both education and one’s profession later in life. For a child with learning disabilities, difficulties with the normative education system and failure to meet expectations frequently results in feelings of inadequacy. Superpowers grant an individual the ability to affect change or exert influence over an environment they might otherwise be powerless in.

Focusing on the notion of changing or influencing one’s environment, we examined the different ways the word “environment” could be interpreted. We were particularly drawn to the notion of the environment as a social realm, a physical space and an ecological system.

Social Realm

Personal computers and cell phones have become such common staples in our lives that texting and other social media exchanges via electronic mediums have dominated, and in some cases replaced, face-to-face communication. These interactions are particularly popular among younger generations for their convenience, instant gratification, lack of emotional accountability and exhibitionistic platforms. We wanted to explore ways to move social media actions such as “liking” and “re-tweeting” from the virtual world to the physical one to facilitate more enduring connections.

Physical Space

We typically think about a physical space in terms of its functional utility. Is it big enough? Does it fit our needs? Does it look okay? We often forget that each space, like a person, has a unique identity that has been shaped by its physical form, social interactions and history. While we often connect emotionally to a space’s identity, we typically only realize it when it ceases to exist. As we were working with Canada Place’s roof fabric, BC Place, another iconic Vancouver structure, came to mind as an interesting example of this phenomenon. Following the transformation of the stadium’s pillowed, inflatable dome into a crown-shaped, retractable roof, the building felt strange against the downtown skyline despite the fact that the operations and other infrastructure remained the same.

KGMS’ recent relocation may have resulted in a similar emotional disruption in the students’ academic life. For children with learning disabilities, such a change can be particularly upsetting as school may already serve as a source of anxiety. To help the students rebuild their sense of school community, we brainstormed ideas that would encourage them to connect not only to each other, but to their physical surroundings as well. It was imperative that these children felt like they belonged to the school and that the school belonged to them.

An Ecological System

In addition to promoting upcycling, we wanted to influence how the students related to the environment. We frequently regard ecology as an abstract thing rather than as living systems. The danger in this characterization is that it reduces the environment and its resources to passive commodities for us to trade and use. We cease holding ourselves accountable to it. To combat this practice, we explored ways in which the KGMS space could play a more active role in the students’ daily interactions, increasing their attachment to their environment.

Project Concept and Design

Combining social media exchanges with the act of graffiti, we came upon the idea of using tangible symbols, similar in aesthetics to apps and icons, to create a social forum that enabled students to influence both their physical environment and each other in manners similar to how they would in the virtual domain. The Tag Project, which consisted of three-dimensional, reusable symbols that could be affixed to an object or surface directly or with the aid of a clothespin, would allow KGMS students to lay claim to or create a dialogue about their surroundings without physically damaging or adversely affecting others’ enjoyment of it. Students would use these symbols to “tag” or comment on an object or area. Other students could agree, disagree or alter these declarations by moving, adding to or subtracting from the original tag (Figure 1).

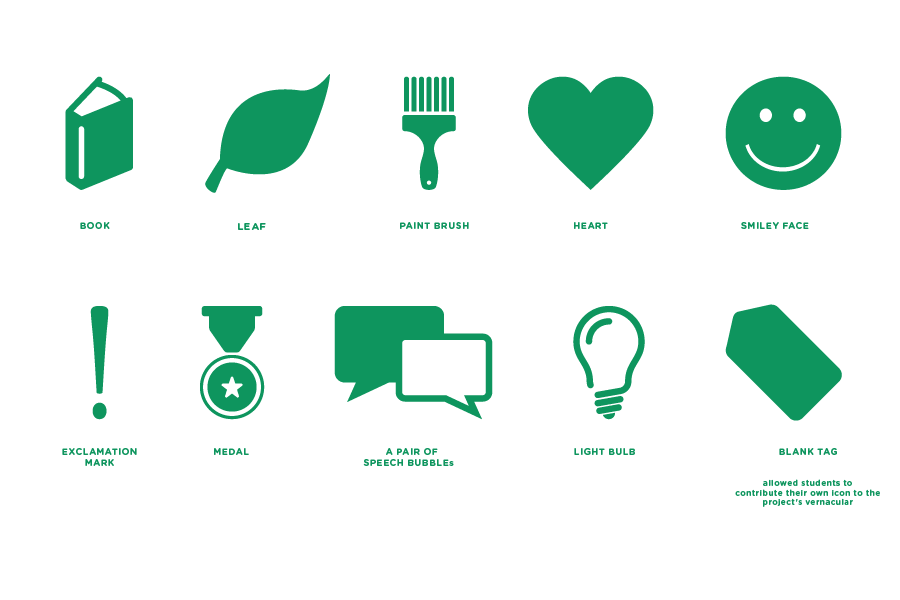

To promote The Tag Project as a cohesive kit for a single KGMS classroom, 60 tags and 60 wooden clothespins were packaged together in reusable, recyclable plastic containers repurposed from 4-litre milk jugs. The kit contained 6 multiples of each of the following tags :

- a book,

- a leaf,

- a paint brush,

- a heart,

- a smiley face,

- an exclamation mark,

- a medal,

- a pair of speech bubbles,

- a light bulb, and

- a blank tag, which allowed students to contribute their own icon to the project’s vernacular

The tags featured positive or neutral symbols that were suggestive enough to express clear opinions when used in isolation, but ambiguous enough that their meanings changed when used in conjunction with other symbols. Negative symbols were omitted to prevent misuse or bullying.

Conclusion

The greatest difficulties in any design project originate from the limitations imposed on designers by the user, materials and production requirements. This project was no exception. Rather than stifle us, however, these constraints allowed us to grow, as we were required to exercise more creativity and make smarter choices with fewer resources and liberties. In addition to the valuable knowledge gained through the experience, the Tag Project resulted in:

The greatest difficulties in any design project originate from the limitations imposed on designers by the user, materials and production requirements. This project was no exception. Rather than stifle us, however, these constraints allowed us to grow, as we were required to exercise more creativity and make smarter choices with fewer resources and liberties. In addition to the valuable knowledge gained through the experience, the Tag Project resulted in:

- an image-based conversation forum that complemented the KGMS students’ learning style;

- an additional teaching and feedback tool that the KGMS faculty could use to initiate discussions;

- a design aesthetic that pays homage to local fabric roof structures such as BC Place and Canada Place, the source of the product’s material;

- minimized waste production through the use of reclaimed materials in both the product and packaging;

- a quick, low cost and efficient manufacturing process that could be duplicated on a larger scale; and

- absent fixed equipment costs, a standalone classroom kit that could be produced for less than $10 in labour and new materials.

By employing various participatory design methods early on in the process, we were able to transform the project constraints into key features that added value to our design with potentially “positive, long-range consequences.” [4] We achieved this by according equal if not greater value to the opinions of our co-creators throughout the design development process, rather than our own. By allowing the voices of the KGMS students to direct the project rather than merely inform it, we were compelled to design directly for their needs rather than our interpretation of their needs.

By employing various participatory design methods early on in the process, we were able to transform the project constraints into key features that added value to our design with potentially “positive, long-range consequences.” [4] We achieved this by according equal if not greater value to the opinions of our co-creators throughout the design development process, rather than our own. By allowing the voices of the KGMS students to direct the project rather than merely inform it, we were compelled to design directly for their needs rather than our interpretation of their needs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ellena Lawrence for her contribution and Hélène Day Fraser for her expertise and support during this project. We would also like to thank the students and staff of KGMS for their valuable insights and enthusiasm.

References

- [1] Forlizzi, J. The product ecology: Understanding social product use and supporting design culture. International Journal of Design 2(1). 11–20.

- [2] Kenneth Gordon Maplewood School. Retrieved from: http://www.kgms.ca.

- [3] Koskinen, I., Zimmerman, J., Binder, T., Redstrõm, J. and Wensveen, S. Design Research Through Practice: From the Lab, Field, and Showroom, Morgan Kaufmann, 2011.

- [4] Sanders, E.B.N. and Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscape of design. CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts 4(1). 5–18.

- [5] Sanders, E.B.N. and Westerlund, B. Experiencing, exploring and experimenting in and with co-design spaces. in Nordin Design Research Conference 2011: ‘Making Design Matter’, (NORDES, 2011), 298–302.