Violence and aggression suffered by healthcare workers “has become a significant problem in healthcare professions” [3], causing both physical and mental consequences for workers and wider systemic issues for the healthcare industry as a whole. Violence, in this context, is defined as “violent behaviour that is intentional, or not intentional due to illness or injury, or where the aggressor lacks the mental capacity to demonstrate intent” [2]. Violence can be caused by patients, their family members, visitors, or others, and is often not seen as violence because it is not considered intentional. Negative impacts of this understanding include: a perception that reporting violent incidents does not result in any positive improvements, a perceived lack of support from administration, and the fear of being stigmatized after a violent incident. Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) has collaborated with Emily Carr University to seek a solution that will decrease the amount of violent incidents suffered by workers, and therefore foster a safer working environment.

Research Questions

In collaboration with Lauren Henderson, we decided to reframe this project and focus our research on the post-incident reporting process healthcare workers go through. We decided to focus on reporting because 91% of healthcare workers agree that violence is underreported, with only 28% of verbal abuse and 57% of physical abuse reported in writing [1]. Without reporting, there is a normalization of violence and a lack of clear data to generate improvements. Reporting can bring an increased awareness of the issue, which can create more support for healthcare workers, more accurate research, and ultimately more funding for a more effective violence prevention program.

Research Methodology

For our primary research, we conducted co-creation sessions with nurses, management, and supervisors from different wards within VCH. We decided to probe for the barriers that prevent reporting both systemically and socially. We did this by having one activity that probed for systemic methodology used for reporting an incident, and another that probed for gaps surrounding understandings of to whom the healthcare worker should be reporting, to whom they actually report, and to whom they would ideally like to report.

Findings

We found that there were both systemic and social barriers that prevented healthcare workers from reporting violent incidents. Systemic issues began with the lack of a centralised reporting system. Workers used both paper-based and electronic-based reporting systems. We also found that meetings, emails, and casual chatting were methods used for communicating about violent incidents. The reporting process is also very lengthy, which is a problem because nurses are time-limited and task-driven. As one of our participants said, “if an incident isn’t reported the day of, it’s just not going to be reported.” Another major systemic issue was workers not knowing what exactly qualifies as an incident requiring reporting, and why reporting is important. One of the nurses shared an experience where she reported by calling a number, and received an automated recording device. She indicated that she was likely not to report again, since she didn’t know whether something was done about her report or where her report went after it was filed.

There were also many social issues that participants brought up during the session. The engrained care culture in the healthcare sector was a prominent issue, as workers would rather take care of their patients than themselves. The participants also described a lack of perceived support from the administration in the reporting process. They mentioned that their emotions post-incident could be as extreme as feeling degraded when filling out police and medical reports, and feeling stupid “because of what you didn’t do right.” Other emotions brought up during the reporting process include the workers feeling: overwhelmed, frustrated, anxious, confused, hurt, and lonely. Some positive points were also brought up, however, such as the strong sense of comradery nurses feel with each other, and the likelihood of informally reporting an incident that has occurred.

Thesis

Considering the problem space we’ve been presented with and the information from both our secondary and primary research, our goal became the creation of a centralized reporting app that promotes a positive reporting experience by establishing a sense of action, transparency, and community. The sense of action is needed to address the issue of workers feeling like nothing is being done after they file a report, the sense of transparency to rectify the problem of workers not knowing where the report goes, and the sense of community to combat the engrained care culture and stigma around reporting.

Conceptual Development

To fully imagine the users’ needs, we created storyboards and personas that helped us to visualise a scenario that would involve all the stakeholders — the nurses who experienced the violent incident, the co-worker who learned about the incident, and the supervisor who received the report.

This way, we were able to think about our app in a holistic manner, embedded in the larger system of use.

While ideating, we constantly checked our ideas with the thesis and objectives to ensure that the solutions we were creating were fulfilling the needs of the users. The visual aesthetic of the app needed to be one that was calming to workers who had just suffered a violent incident, but still engaging so users would understand the importance of the report. The combination of a light blue and dark red for the interface was selected, accompanied by a slab serif for the heading and humanist sans for the body text. These choices were all made with the intention of reinforcing a calming and engaging effect. Many iterations of the wireframes and user flow ensured that the interface would be as simple as possible. The interactivity gestures were designed to boost efficiency, using more swiping than tapping, and more drop down menus than new pages.

Final Solution

For our final solution, we created an app for healthcare workers for filing and checking on their reports, which also educates users about the importance of reporting. We imagine this app to be a part of a larger digital hospital system that would track patient information, charts, nurse schedules, and more. We decided on an app format because we realized the potential for a more efficient reporting process due to a wealth of data already stored in the hospital system, as well as the potential for immediate feedback on reports. These functions could not be provided using a paper-based reporting system. We imagine nurses picking up a tablet from the nursing station at the beginning of their shift, and logging into their account. The tablet would be about the size of an iPad mini, which is small enough to fit into the pocket of their uniform pants.

Upon logging into the app, the home screen will appear and offer options for filing a report, checking reports, and an “about” page with information on what qualifies as violence and why reporting violence is important. There is also a top bar that shows the user’s name and time, and icons to access their messages and notifications, and a log out button.

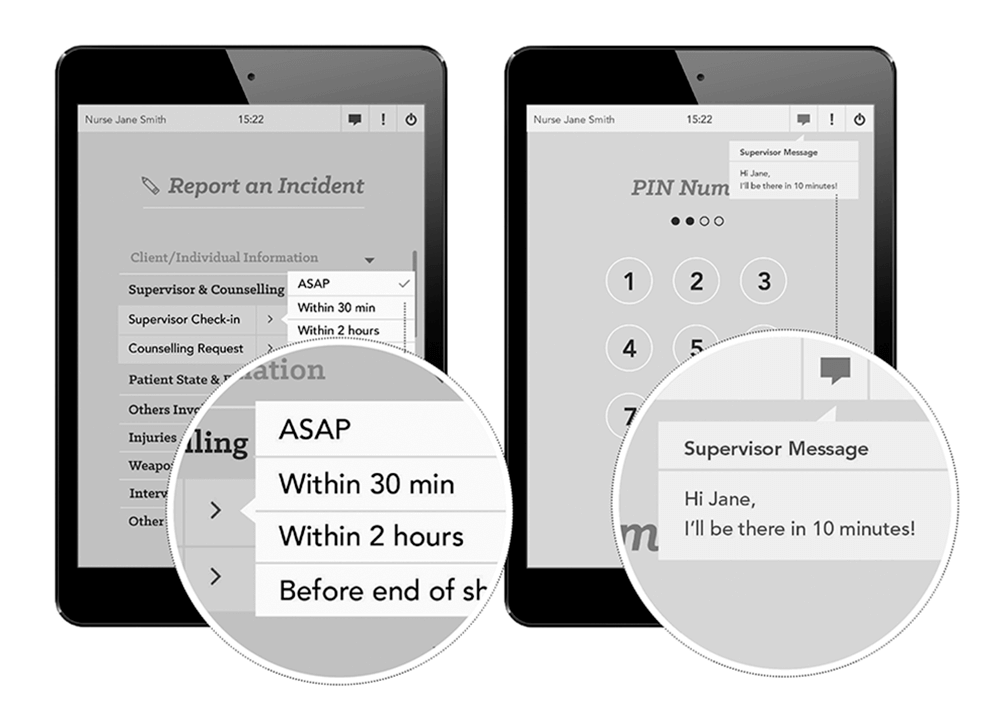

For filing a report, we have streamlined the form down to eight drop-down categories that the user can access by swiping down to fill it out. This reduction of required information input is possible because of the data already stored in the wider electronic system, and increases the efficiency of filing a report.

Users can also request a supervisor check-up or a counselling appointment on the reporting form, or on the check-in notifications that will periodically appear through their shift. If requested, supervisors can then use the messaging system to let the worker know when they can check in with the worker. Counselling services can also use the messaging system to make an appointment with the worker. This immediate feedback and notification system addresses the issue of workers not knowing if anything will be done about their report. This app also reminds them that the options for supervisor check-ins and counselling appointments are always available.

Upon submitting the report, a page will appear to thank the worker for reporting, and show data visualizations on reporting and incident rates in BC. This function reinforces the idea that their contribution is combating the wider problem of violence, and reduces the stigma that workers might feel if they think that they are the only ones reporting.

Other workers who share the same patient will receive a notification of the report. They can view and “appreciate” it, so that the worker who filed the report will feel supported, and feel like their contribution is benefiting their colleagues. This aspect of the app aims to build a sense of community and support, and to emphasize the benefits of reporting to build awareness and prevent future violent incidents.

In addition, there is an option for workers to track a report they’ve filed to see where it is in the administrative process. When they select a report, the information and timeline will appear, which will indicate the administrative phase the report is in. This feature addresses the issue of workers being unsure of where their report is, or if anything is being done about it. They can also access reports filed by colleagues who share the same patient, so they can be updated and aware of any incidents.

There is also an “About” page to inform workers about what qualifies as violence and aggression to VCH, and the patient privacy policy. They can also swipe right to learn why reporting is important to themselves, their colleagues, for research, and for funding. This information page addresses the problem of workers not knowing what to report and why they should report.

Conclusion

This centralized reporting app that promotes a positive reporting experience by establishing a sense of action, transparency, and community, will hopefully result in reporting rates increasing, thus creating a safer workplace for healthcare workers, and ultimately increasing research and funding for the violence prevention program. For this project, having a clear thesis to refer back to and thinking about the solution in the context of the system proved to be crucial. This process reinforced user-centered thinking and designing to ensure that the workers’ needs were met. Through the process we made some major decisions, such as deciding on making an app, and using the app to share patient information between nurses. These decisions were validated through our future-oriented approach, in which apps and tablet usage will be normalized, the hospital data system will be electronic, and where patient information sharing would ultimately prevent violence. Other decisions included narrowing down which features to highlight, in this case, those that perpetuate a sense of action and efficiency using the immediate feedback and notification system.

If we were to start this project again, and given more time, we would have explored different options that are not just future-oriented, but which could also be implemented in the present. We would have also created solutions directed at all the stakeholders in the entire system, including the supervisors, managers,

and charge nurses. As well, we would like to have been immersed in the healthcare environment to fully understand the needs and limitations of the users.

Commentary

When collaborations between the healthcare industry and communication designers occur, projects such as these bring new processes and perspectives to both industries. While the healthcare industry can benefit from design thinking and creative solutions, designers can benefit from working with a problem space that requires evidence-based, user-centered, and participatory design. These practices are especially relevant now, as there is a “paradigm shift currently occurring in design practice — that is, away from designing for people and towards designing with people” [4]. As a system, we imagine our solution will be relatively easy to integrate into a wider system of electronic healthcare records in the future. Creating something interactive for this project was also beneficial in that it pushed us to consider the future, where such interactive systems will be more widely implemented. Although there is an argument that technological interactions limit personal interactions, the solution we have created is meant to enhance human interaction by making communication more efficient and effective, rather than replacing it. A centralized reporting app such as ours will hopefully achieve all of these goals, as well as help our end user group of health care workers stay safe in their working environment.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Deborah Shackleton for providing guidance and support, Jonathan Aitken for facilitating the Violence in Healthcare project with Vancouver Coastal Health, and the workers at VCH for participating in our project, attending our co-creation session, and sharing valuable insights.

References

- [1] British Columbia. Occupational Health and Safety Agency for Healthcare in British Columbia. Research Update: Violence in Healthcare Worker Survey. Vancouver: PHSA, 2009.

- [2] Eastman, B. and Schecter T. British Columbia. Provincial Health Services Authority. “Behavioral Care Planning for Violence Prevention.” Provincial Violence Prevention Curriculum. Vancouver: PHSA, 2011.

- [3] Rippon, T.J. “Aggression and Violence in Health Care Professions.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 31, 2 (2000), 452–460.

- [4] Fulton Suri, J. Involving People In The Process. http://designingwithpeople.rca.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/Jane-Fulton-Suri-for-with-by.pdf.